The Price is Right

More like, "how much again?" Certainly about as clear as mud in several modes. #shippinainteasy

“Seems like everybody's got a price

I wonder how they sleep at night

When the sale comes first and the truth comes second…We just wanna make the world dance

Forget about the price tag”- Jessie J

Here in the third edition of Beyond Logistics, we cover a topic that should be near and dear to every shipper, carrier, and 3PL’s heart - pricing! It’s amazing when you dive into pricing across modes how (unnecessarily) complex it can be. Like Jessie J, many would love to just forget about this tricky little thing called “pricing” and just dance around, but we can’t. It’s pretty important, as it lies at the crossroads of supply and demand and reflects the relationship between company and customer, shipper and carrier. And pricing impacts the profitability of every company.

This piece started with the idea of ranting about the painful, archaic, overly complex, NMFC-based pricing seen in the less-than-truckload (LTL) arena. Simply writing on the ins and outs of LTL pricing alone could go on for 10+ pages, but we’ll spare you (most of it) here. Then the thought was for an extensive comparison across all modes, but we opted to concentrate instead on broad concepts, key takeaways, and write in more detail just about TL, LTL, ocean, and parcel. Still a good bit to chew on.

Prices higher than Snoop Dogg on a 747

Let’s first briefly talk about price levels, as pricing pain helps drive pricing curiosity and inquiry. High prices are currently grabbing headlines due to rising CPI reported last week (chart below through June 2022) - yeah, that’s a sharp spike. So, it looks like a significant Fed rate hike now almost certain. Good. Rates have been too low for too long.

CPI ain’t no lie

What’s behind that spike in the chart? “Short version” is that there have been long-term (labor) supply headwinds brewing under the surface for years (we heard a lot about the shifting labor demographics from Ken Gronbach at a conference a few years ago), and then the government’s simultaneous actions of restraining business/work activity and handing out money to goose consumer demand levels formed the perfect recipe for significant inflation across the board (more dollars chasing fewer workers, goods, and services). We’re now in a period of trying to right-size it, but “right-sizing it” inevitably means that demand must fall (aka “recession”), and we live in a world where nobody wants to self-correct, nobody thinks they should take a breather, and a temporary (healthy) lull in activity is somehow viewed as bad and feared (see last month’s post for a few more thoughts on “recession”).

Back to pricing - how it works

When you buy something at a store, it’s easy. You want to know how much some cold brew coffee is and you find Lucky Jack’s “Old School” cold brew on the grocery store shelf for $3.99. That’s the price. You pay $3.99 and walk out with your coffee. Sometimes they’ll add sales tax, and sometimes not, depending on where you are.

When buying a good online, pricing’s slightly more involved, as the seller now needs to get it to you. So, we usually see some sort of extra charge for shipping. The price of the item (unless “free shipping” is offered) is therefore not the $34.95 quoted for that collagen protein (which you can add to your coffee for a good time), but is now over $40, including shipping.

Concert tickets take it to yet another level by tacking on service fees. Ticketmaster started this years ago, and now everyone’s doing it. For example, tickets to a local comedy show say $30 each on the Improv’s website, but that $120 for four tickets is just the beginning. Tax of $8.40 and service charges of $18.60 bring the actual total to $147 (or $36.75 each). That’s 22.5% higher than what was quoted. We see this also at hotels with local and state taxes. I stayed in downtown Chicago the other week, where the hotel quote online was for $229, but the bill after fees/taxes was $280.58. Another 22.5% jump. Coincidence? Or is there something to the surcharges/fees being equal to 18% of the total spend? Just glad they don’t have fuel surcharges right now!

Well, same with freight. The amount a shipper pays can vary substantially from the initial quote received or from what they may perceive to be the price. And to make it more difficult, these added fees and surcharges (aka accessorials) are not uniform across modes or carriers within each mode. So, work has to be done by the shipper to not only understand what you’re paying but understand what the pricing competitiveness of each carrier actually is.

Point-to-point full-load pricing - e.g., ocean freight, truckload

When you’re shipping enough to “fill a truck,” you not only get a better price, but it’s a simpler price - another benefit of volume. Anytime a carrier can easily assign costs to your movement, it removes a lot of the fuzzy math behind pricing and should allow for a better rate for the shipper. At the same time, the shipper has a better idea of how much it costs to move their freight so can push a little harder in pricing negotiations. The three main modes of point-to-point full-load (trailer, container, or rail car) are ocean freight, truckload (TL), and rail. We’ll briefly address the first two here.

The simplest of these is truckload. And we’ll stick to dry van for-hire truckload for this example. Flatbed, specialized, reefer, and dedicated all have some differences. In short, charges are on a per-mile basis, which may be adjusted based on the length of haul (higher per-mile rate at shorter lengths of haul, similar to the idea of minimums that we’ll address later). And then for past roughly 20 years (originally in the mid-90s, but mostly since the early ‘00s), a fuel surcharge is added based on the price level at the pump.

Ocean freight (containerized) also appears pretty simple in terms of a point to point container rate + BAF (bunker adjustment factor - aka fuel surcharge). But the carriers play around with the BAF more than truckers play around with the fuel surcharge. It’s mostly games with optics, though, as we see carriers remarkably land very close on the all-in rate. In addition, in periods like we’ve been in the past couple of years (tight capacity), additional surcharges will be levied, like a congestion surcharge. We saw this back in 2002 and in 2014-2015 during other periods of port congestion (due to labor issues). When supply/demand loosens, these extra charges tend to disappear.

Network (partial-load) pricing - e.g., LTL and parcel

When a shipment doesn’t take up a full container, full trailer, or full rail car, a carrier needs to consolidate your freight with other shippers’ freight to move through their network. This is essentially the movement of packages and pallets, plus odd-sized and oversized pieces that don’t fit into a box or on a pallet. Carriers/logistics providers in this general area operate hub-and-spoke networks (to create synthetic full-loads on linehaul) - including LTL, parcel, LCL, and airfreight.

Rather than point-to-point pricing (regardless of weight or cubic dimensions), pricing is set off of tariffs (or a rate card) that look at the cross-section of weight/dimension and distance. Based on a shipper’s volume, they can negotiate discounts off of this “retail” rate. When looking at tariffs and discounts, JoS. A. Bank usually comes to mind, for if you’re not getting a large discount off the published tariff (or 3 suits for the price of 1), you’re likely overpaying.

LTL is the most unnecessarily complex, as its core basis for pricing still relies on the old NMFC (National Motor Freight Classification) system - an institution of yesteryear that just won’t seem to die. But it will. Ever heard of a hundredweight? I hadn’t before I entered the LTL world. Rather than price per pound or per ton, carriers look at pricing based on hundredweight (or for every 100lbs). The class system was set up a long, long time ago before it was easier to get proper dimensions of freight. The thinking was that freight differed by ease of handling, stowability, density, value, and other factors that needed to be taken into consideration (on top of weight). So, carriers have been assigning a class rating (50-500) to each commodity being shipped. On one end of the spectrum (Class 50), you’d have something heavy, dense, low-value, hard to damage - like nails. And on the other end (Class 500), you’d have something like ping pong balls, which took up a lot of space and didn’t weight very much and were easy to damage. These classes then became a multiplier of sorts to the weight (or hundredweight) of the shipment.

But today, it is clear that carriers sell space, not weight (one carrier once told me that 98% of their loads cube out before weighing out). And with advancements in dimensioner technology and the widespread installation of dimensioners across LTL service center networks, we expect a continued move in this direction to ultimately eliminate the classification system and reduce complexity in pricing.

But it will still remain complicated. Just look at an LTL rules tariff - 135 pages at Saia, 143 pages at Estes, and 232 pages at Old Dominion. That alone should signal the complexity involved in shipping a pallet of LTL freight with any carrier.

Now, some shippers are choosing a simpler route already to bypass the class/tariff system, looking to cubic foot rates and pallet rates, for example. These both target dimensions, by the way.

Parcel pricing is also a doozy for shippers - but for different reasons. Back to the service guides - at UPS, it’s 158 pages. At FedEx, it’s 185 pages. No class system here, as the (effective) duopoly of UPS and FedEx pushed dimensional pricing years ago, just as they pushed electronic billing, electronic tendering, and electronic communication. Still a lot of paper floating around LTL docks - not so much at a small package facility.

Back to pricing, it is made complicated by the sheer number of accessorials/surcharges (over 100) these days. UPS and FedEx have really been able pinpoint the costs in their network, and every little thing that adds cost to a package moving from origin to destination is viewed as a revenue opportunity and tied to a surcharge. The difficulty for shippers is tracking all of this and identifying the all-in costs ahead of time. For example, a shipper may think his packages are costing $14 each, but the bill may come back with an average cost of $18+. The good news re: accessorials could be that there are accessorials a shipper can identify and eliminate by doing things differently on the front-end (e.g., packaging).

Peak surcharges are fairly new, and dim charges and oversized charges have changed quite a bit with the significant growth in e-commerce the past few years. There is so much confusion when it comes to parcel pricing these days, even among those “veterans” who have been in space a while. And the teeth baked into the very long (in page length) multi-year contracts many shippers sign (to get a deal) increase switching costs between carriers. Many have penalties for early termination and/or prohibit re-bidding the freight for a certain timeframe.

Note that U.S. Postal Service package pricing is simpler with fewer negotiated contracts. I think they should actually increase pricing complexity to help dig their way out of the red - more surcharges = more money.

Lastly, minimum charges - these apply both to LTL and parcel networks and account for a significant amount of volume. At some point, no matter what your “discount”, all freight and all packages converge on a single number - the minimum charge. So, the lighter the weight, the higher the revenue/lb. This is something that should really hit home for e-tailers, who have lighter-weight shipments, on average.

Fuel surcharges differ by mode (and by carrier)

Roadway was the first carrier I can remember introducing a fuel surcharge (fsc) back in 1996. It was a marked change from the carriers bearing all the fuel price risk to sharing the risk with customers. Of course, fuel prices were more or less flat for most of the ‘80s and ‘90s, so this didn’t become super important until the ‘00s, when the commodity saw several periods of significant increases.

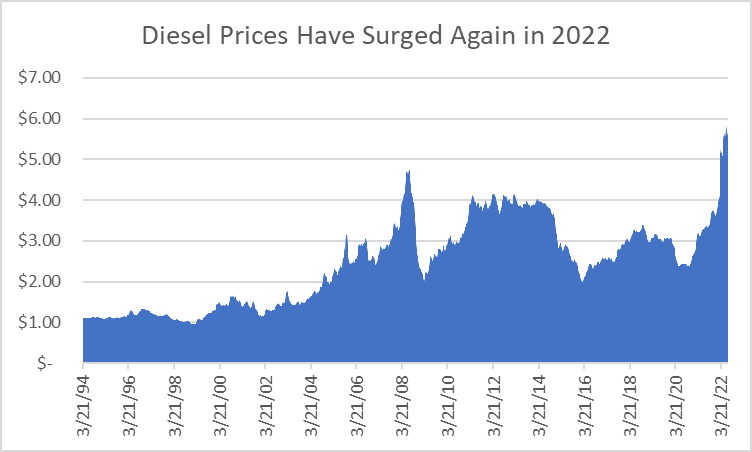

Diesel prices are near all-time highs (chart below), so this is a very important piece of the pricing picture today. Diesel at $5.43 for week ended July 18, 2022, down 7% over the past month but still 62% higher than a year ago and 50% higher than at the start of 2022.

Source: EIA, data through 7/18/22

The mechanics vary from mode to mode and even within modes there are carrier-specific differences. And then when you get into contracts, there is room for further variance. Some (larger) shippers have their own fuel surcharge tables that need to be factored into rate discussions, as they force carriers to recalculate the base/all-in rate using their surcharge table.

Truckload - adjusts weekly - fsc based on brackets (cents/mile rate adjusts with move in $/gal at the pump - often on $0.05 or $0.06 increments to align with mpg) with a floor (sometimes $0, sometimes $1.20/gal or more). Based on EIA On-Highway Diesel national average (or regional for some regional fleets). This is most transparent, as a shipper can tie the cost of fuel up and down directly to the cost to move their freight.

LTL/parcel work the same - adjusts weekly - fsc set as % of revenue…now 40.8% at R+L and 40.75% at XPO, for example, based on $5.57/gal last week. Within parcel, Ground and Air have different surcharges, but mechanics the same. As of the most recent week, effective 7/18/22, UPS Ground’s fuel surcharge is 17.75% and domestic air is 20.0%. FedEx is close, with FedEx Ground at 19.0% and FedEx Express (domestic package) at 20.0%.

Ocean freight - adjusts monthly or quarterly, depending on carrier. The fsc is quoted as BAF (bunker adjustment factor) - one source is Bunkerworld’s fuel price index for 0,5% Sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO) for the BAF calculation.

So whether you’re talking per-mile brackets, % of total, or BAF, they’re all generally negotiating tools - some are negotiable, and some are not. Depends on how big of a shipper you are. And sometimes, it just depends on where we are in the cycle.

So, we’re back again to “what’s the all-in price?” Because at the end of the day, if a shipper wants a fuel surcharge cap or an alternative fsc table, it will result in a higher base rate. Or if they are content with carrier’s fuel surcharge, they should be able to get a better base rate negotiated, all else equal.

Pricing outlook generally higher

Now a little bit about where we see pricing for each mode heading into 2023, given the inflation mentioned above. Then what’s driving the rates and what can be done about it by shippers.

Important distinction to make when talking about pricing - spot vs contract. The majority of freight moves under negotiated contracts, but most of the available data sources that look at “real-time” price moves are referencing the transactional spot market. Granted, spot trends lead contract trends, but you need to be careful in terms of how you let them filter into your assumptions and how to apply them to your own negotiations. And not all modes have active spot markets (e.g., LTL and parcel) - just “retail” rates.

Truckload has a healthy spot market with lots of activity, but even the main load boards - truckstop.com and DAT - don’t accurately reflect TL pricing, especially when you try to compare the national average to the price you’re paying in a specific lane, like Miami-Baltimore.

Ocean freight has had more spot recently, as container lines took advantage of a bonanza in 2021. See this recent interesting piece from ocean shipping expert, John McCown. Publicly available rate data is not always reliable. It can be useful, though, even if not accurate. But you must understand how to properly use it as a tool. For us, it’s best directionally without focusing too much on the specific rate quoted.

At a basic level, driving the rates higher from the cost side right now are labor, fuel, real estate, and supply/demand still favoring the carriers.

Outlook by mode

Truckload - spot rates have been down ~25% y/y for the past few months, while contract rates continue to rise 5%-10%. Expect to hear more these next two weeks, as the publicly traded TL carriers report earnings and provide their updated outlooks. Spot rates seem to be leveling off, and we’ll see how the growth in Class 8 production makes its way into the supply side through the rest of the year. Being most exposed to consumer spending, we see more downside in TL rates than upside.

LTL - we saw in 2019’s industrial recession that carriers could hold the line on pricing through a period of declining volumes, and we expect to see that again when LTL volumes lighten up. Right now, we’re looking at mid-single-digit rate increases for carriers. Even in a downside volume case, we have a hard time seeing anything below a 2%-3% increase over the next year.

Parcel - UPS and FedEx continue to aggressively push rate increases and targeted accessorials. And even after reasons for certain accessorials disappear, they’re still able to hold them, as discussed in this recent article. Shippers most exposed will be those with “undesirable” freight - or non-conveyables. Expect rates to be up mid-single-digits, including accessorials.

Ocean freight - an industry notoriously famous for a lack of price discipline that led to many years of losses (operating below costs) until government actions forced the carriers into record profits the past two years (thanks to the demand stimulus coupled with the supply crunch), there’s a lot of debate about where ocean rates go from peak levels. Well, contract levels are just now at peak, as spot has retreated significantly from its $20K-$25K peak for an Asia-U.S. container move last year to more like $6K-$9K today. We’re seeing contract rates and spot rates converge. Will spot rates continue to fall? And will that drag contract rates down significantly next year? Not until there’s peace on the West Coast for sure. And even then, it may be different than past cycles - as discussed in this excellent article from JOC - CMA Big to Fail, where it’s argued that the carriers will now do a better job controlling capacity and pricing. TBD.

Why can’t we all just get along?

Saw this quote (below), and unfortunately what immediately popped into mind was shipper/carrier relationships.

“I love you. I hate you. I like you. I hate you. I love you. I think you’re stupid. I think you’re a loser. I think you’re wonderful. I want to be with you. I don’t want to be with you. I would never date you. I hate you. I love you…..I think the madness started the moment we met and you shook my hand.”

― Shannon L. Alder

It’s unfortunately been generally adversarial these past 40 years since deregulation. The “I love you” moments for carriers are during cyclical freight downturns, when freight is scarce, and they just want their trucks (or ships or planes) full. For shippers, the “I love you” comes in strong freight markets whenever the term “Shipper of Choice” is used (pick me! pick me!). I’m sure you’ve heard it used a lot lately.

What about contracts? Doesn’t that drive better behavior? Contracts are not what an outsider might think. They’ve been referred to simply as “a mechanism to set price and terms,” as they (in most modes) contain no volume commitments from the shipper or capacity commitments from the carrier (even if some level is implied in the negotiated rates). The lack of commitment speaks to the lack of seriousness in the relationship, or the transactional nature of even a contractual relationship.

Besides the natural ups and downs of freight cycles, much of the historical shipper/carrier tension circles back to communication. It’s been for years a contentious and mistrustful relationship with each side holding something back (i.e., information sharing). Increased quality of communication improves transparency on both sides, making it more likely for a mutually beneficial outcome (a healthy longer-term relationship). If the carrier knows what it’s getting, then less cushion needs to be built into the quoted rates for variance. And if the shipper knows what they’re paying, there’s less likely backlash from the finance folks when they look at transportation expense at quarter’s end.

Carriers like to make it tough

Especially today. Carriers have an incentive to obfuscate price and make it complicated for shippers, as margin lies in complexity. And shippers may be so frustrated or feel so helpless in some cases with all the rules and surcharges that they just throw up their hands and stick with their incumbent carrier. This is good for the incumbent, not the shipper.

“It's funny. All you have to do is say something nobody understands and they'll do practically anything you want them to.”

― J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

But carriers can also make it hard on themselves - harder than it needs to be. They first need to understand their business and their costs. If they don’t, they “think” they’re making money, but when they close the books at the end of the quarter, the margins are much worse than expected. That implies a disconnect somewhere in the system. We’ve seen this time and time again. And it usually goes back to insufficient or improper cost allocation.

I’ve had LTL carriers tell me in the past that they price off of variable costs, because in a network business, the trucks are already moving each day, and getting one extra shipment just needs to exceed its variable costs to be profitable. While that may be true for that one incremental shipment, if that pricing philosophy pervades the whole organization, then every shipment ultimately gets priced off of variable costs, and none of your customers are paying for the fixed costs/overhead. That’s the kind of stupid thinking that kills companies.

Whatever the price, though, it better be backed by reliable service. Shippers will always pay more willingly for quality service. While pricing is important, competing solely on price (especially on low price without a low-cost operating model) is not a good long-term strategy. Shippers ultimately want their freight moved reliably in a timely manner from one point to another, damage-free. If this is not the case, it doesn’t matter what the price is. To use a restaurant analogy, a $0.99 steak that makes one sick may get someone in the door once but will not create a happy or recurring customer, where a $69.99 steak executed to perfection will bring repeat business and more profits. Create value, and price as you need to in order to deliver a quality product. Never apologize for price. Service. Service. Service. I aim to make that the primary focus at all of our companies.

“The bitterness of poor quality is remembered long after the sweetness of low price has faded from memory.”

- Aldo Gucci

As for what’s new on the pricing front…

It was recently reported that Old Dominion is now testing all-in one price, what it calls One Rate, One Time. We applaud the goal here, and it will be interesting to see the level of adoption by customers and whether any competitors follow suit. Getting to this point was not easy, though, especially to be done in a thoughtful, profitable way, so I’d take the “over” on others rushing out with something like it.

Surcharges for CA shipping may increase, and we may see surcharges imposed for other states, if they make trucking more complicated and costly as well (we’ve been hearing that NJ is “the CA of the East Coast”).

Shippers playing a new game

While carriers are finding their pricing power and increasing complexity to increase margin, shippers have moved from pitcher to catcher in rate discussions. After years of being in the driver’s seat with respect to pricing negotiations (most of the first 40 years after deregulation), shippers have been punched in the mouth the past couple of years, and we don’t see the pendulum swinging back anytime soon, outside of some cyclical easing from time to time in a fragmented mode like truckload, or potentially in a poorly-managed mode like ocean, if old habits return.

This loss of leverage is a long-term trend…the reversal of another long-term trend…just like near-shoring/re-shoring. And if that plays out over the next decade, pricing pressure will continue upward for all domestic freight modes.

Back to LTL complexity. In LTL, shippers should have the goal of making it simpler, although they don’t seem to want to. We’ve talked about density-based or dimensional pricing for years, and we’ve seen it in practice on the parcel side for a while now. But the LTL industry has been stuck on the old class system mentioned earlier. The response I’ve gotten from carriers has been that shippers are so tied into the old way of doing things, that if one carrier changed its pricing, then the shipper would just use them where the new pricing was advantageous and use their competitors where the old pricing was advantageous. Even though LTL is more concentrated than TL, it is still fragmented enough to disallow quick massive carrier change. In other modes, like parcel and rail, shippers really have no choice and just need to take what’s given to them. But let’s see how the Old Dominion’s One Rate, One Time does - we’re certainly close to an inflection point just from a technology and generational perspective where there will be a push on all sides for simplification.

So what? What does it all mean?

Confusion and complexity compound during periods of stress, making the already-frustrating times for shippers just a little worse.

Our basic takeaways for carriers and shippers (which includes 3PLs) are as follows.

As a carrier, you have to work hard to identify all your costs and flex your pricing to account for extra cost put on you by the shipper. And this all needs to be captured easily via technology and translated into profitable pricing.

In network operations, cost is space, not weight. Trailers almost always cube out before weighing out, so you need to look at both with a priority given to cube, especially now that there’s more technology available to do this more accurately, faster, and cheaper.

As a shipper, you need as much data about your own freight as you can get and share (including weight and dimensions). In contract negotiations, carriers will also want to see a fairly detailed history of shipment activity. And then understand the carrier’s cost profile, as often the biggest savings do not come from switching carriers or “winning” a negotiation to lower rates. It’s most often from doing something different (packaging, consolidations, e-tender) - make it easier for them to move your freight.

Two other ways to save money and optimize your network. 1) Modal optimization - can you use LTL instead of parcel? Intermodal instead of TL? Does air make more sense than ocean? And once you figure that out, 2) network matching - look for carriers whose networks match your network, whose freight flows match your freight flows. And in some cases, as American Eagle is doing, look for competitors or other shippers whose networks can be combined with and/or leveraged with yours for better overall logistics costs.

Pricing is simply determined by five things:

a) service (carrier leverage),

b) volume (shipper leverage),

c) supply/demand balance (external factor),

d) complexity (applies to both shipper and carrier - goes toward costs)

e) communication (in control of both shipper and carrier).

So, whether you’re a shipper, carrier, 3PL, or in another business altogether, think about what’s in your control and where you can improve on the five things above, and see your business (and bottom line) get better quickly.

In Case You Missed It

Beyond Logistics post #1 re: trucking 101/recession chatter —> here

Beyond Logistics post #2 re: life —> here

About the author: Dave Ross currently serves as Chief Strategy Officer at Ascent Global Logistics and EVP at Roadrunner. He is also a Director of Global Crossing Airlines. Prior to his current roles, he was Managing Director and Group Head of Stifel’s Transportation & Logistics Equity Research practice. Based in Miami, FL, he’s also an artist, investor, proud dog dad, and serves on a few select non-profit boards.

** All opinions in this piece are solely those of the author and not intended to represent those of Ascent Global Logistics or Roadrunner or other affiliated entities.