On the Road Again

Trucking 101; where we sit today; fear the "R" word?

“Nowadays everybody wanna talk like they got something to say

But nothing comes out when they move their lips

Just a bunch of gibberish

And motherfuckers act like they forgot about [Dave]”

- Dr. Dre

Sweet hip-hop lyrics aside, some of you know I wrote actively on the transportation and logistics (T&L) space from 2006-2021. For those unfamiliar, it was not an open publication but one limited to our firm’s Wall Street clients and industry executives. I also authored the Cass Freight Index monthly report for a time and was a featured speaker regularly at T&L conferences and events. While winning several stock-picking awards over the years, my focus was always on understanding the industry first, company second, and stock third. Since leaving Wall Street in March 2021, I’ve been working as an executive in the industry and have not published anything until now. These writings will not be a replication of my prior research reports. This instead should be a passing-along of my many learnings, some current market commentary, and applications of lessons in logistics to other industries and fields. Cadence still TBD, just know every writing will be different. Thank you to many of my former readers for encouraging me to re-enter the discussion and share my voice. You rock.

Trucking: A simple hard business

For today, we’ll focus on the U.S. trucking industry. Yes, supply chains are global. They’re complex. Multi-modal. And evolving. All this and more will be addressed in later notes.

Some may think, “what’s so hard about trucking?” Especially truckload (TL). For simplicity, just think of the big 18-wheelers you cruise by on the highway. One of those “big rigs” moving one customer’s freight from origin directly to destination is a basic truckload move. After all, you just pick up freight at point A and deliver it to point B. Simple. Well, spend any time with a trucker, and you’ll quickly realize it is a much more complex business than it may appear, particularly once you start growing the size of the fleet. You’re really managing/balancing three distinct assets that do not move together - tractors, drivers, and trailers. It’s about lane balance, keeping drivers happy and moving, keeping your equipment well-maintained to maximize up-time, and pricing it all well in a market that can be brutally volatile (if you play in the one-way transactional part). Of course, you also have to worry about weather, traffic jams, breakdowns, driver no-shows, and potentially disastrous accidents when driving towards a “simple” on-time delivery.

Trucking accounts for most of the >$1 trillion annual U.S. transportation spend (~80%) and for the bulk of goods movement (~70%). The biggest piece of the trucking industry is the truckload market, of which the biggest slice is the dry van truckload market, which can be split nearly 50/50 into for-hire (e.g., Knight-Swift and Schneider) and private fleets (e.g., Walmart and Sysco - two of the largest). Most of what is written about “trucking” or “spot rates” refers just to the for-hire portion of the dry van TL sector, which is still a few hundred billion in annual revenue. Other sectors (niches), like LTL (less-than-truckload), flatbed, temperature-controlled (aka reefer) - and even parcel - are much, much smaller. Supply/demand and pricing dynamics tend to trickle from the top down, so it is important for shippers and carriers to know what’s going on in the TL market. If the truckload market is tight, it has an overflow impact on other modes, like intermodal and LTL, lifting volumes and pricing for all.

The truckload sector is highly fragmented with over 350,000 active for-hire carriers in the U.S. (354,800, to be more specific, according to the latest data compiled by Tucker Company Worldwide/Qualified Carriers.com). Heard a speaker say once half-jokingly that the only industries more fragmented in the U.S. were landscaping and babysitting. And this is true pretty much around the world. Europe, Africa, Asia, S. America - trucking is dominated by “mom & pop” carriers. This fragmentation and size in the U.S. lends itself to be as close to a “perfectly competitive” market as there is, functioning similarly to a commodity.

This large and fractured capacity pool has naturally led to a sizable freight brokerage industry, allowing shippers better access to these many small, hard-to-reach carriers and giving the small carriers better access to available freight. We could go down the brokerage rabbit hole here but will refrain until another time. Suffice to say, brokers are important, and it is not a winner-take-all industry We see the opportunity for plenty of brokers to grow profitably and thrive over the long run.

And just because truckload pricing may behave like a commodity, it does not mean it’s unimportant. Quite the contrary. Due to the nature of the market, shippers never want to pay $0.01 more than they have to for a truck. But they will pay whatever they have to for a truck, as their business and the movement of the broader economy depends on it. We have been witnessing this live and in color over the past year or two.

Freight rates cooling off

Fortunately for shippers, we saw “peak pain” in the supply chain back in the first quarter this year, and while it won’t be easy or cheap the next year or so, it should not get worse. Of course, the market will relatively tighten/loosen through normal seasonality, and fuel (a significant freight cost component due to fuel surcharges) remains a wild card. But the trend through 2023 is one of easing pressure where we expect supply growth to outstrip demand growth. This is not all good news for shippers, though, because the easing is and will be driven partially by a drop in demand for their goods. Inflation has been the talk of the town this year for good reason. Employment is still tight (though layoffs are beginning), and wages continue to rise - just not as fast as consumer expenses (e.g., food, rent, gas, ride-share), meaning the average consumer can now buy fewer goods with their money than last year. Fewer good purchased ultimately translates into less freight to move.

Reading demand: Manufacturing > Retail

Stepping back to talk about how to take the demand pulse of the U.S. freight sector. There are many data points from various sources, but you can focus on three to get a useful view of how much freight is moving around and sniff out the bigger trucking demand picture. First is rail carload data (a weekly real-time data set on goods movement published by AAR), which has shown y/y declines of ~2%-4% each of 4Q21-2Q22. Usually best to exclude coal & grain shipments, as those commodities often sit outside of normal economic demand and may fluctuate due to weather, harvest, or other factors that do not impact the trucking market. Story is the same either way we look at it right now; volumes lower.

Second is the ISM Index (chart below), as a fairly real-time indicator (published monthly) of the industrial economy. An index reading >50 means we’re still in expansion mode, whereas a reading <50 means the manufacturing sector is contracting. From the chart, we’re still in growth mode (56.1 in May), but slowing growth on its way to contraction as early as 4Q22 but more likely early 2023.

Manufacturing sector growth to continue slowing into 2023

Source: Institute for Supply Management

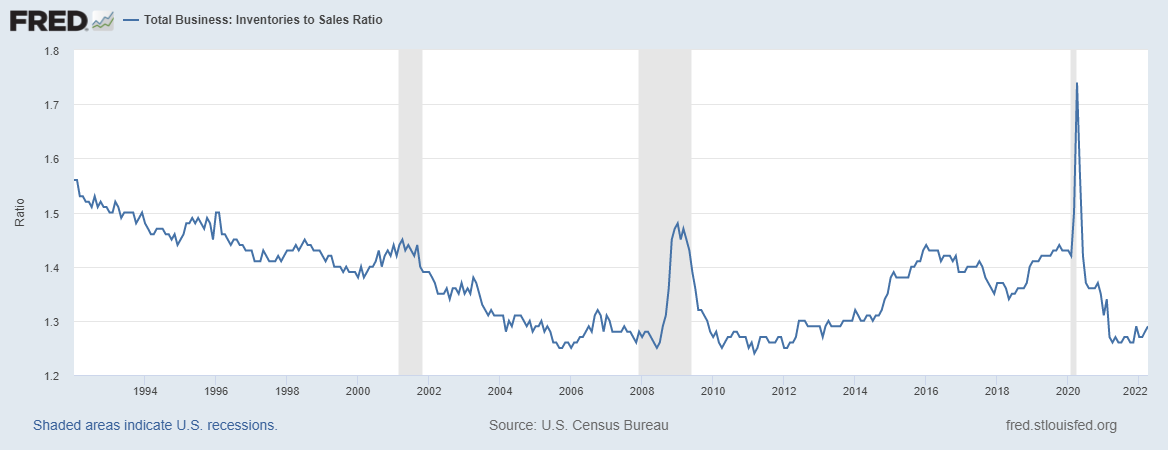

Along with the rail data and ISM Index, we look to the Inventory/Sales (I/S) Ratio as a +/- for freight demand. Because even if manufacturing is growing, for example, if manufacturing inventories are high, growth will be below that of demand. Conversely, if inventories are low, freight volumes will then be “juiced” for a time until normal levels are seen again. With all the fits and starts in the supply chain the last couple years, inventory shortages were the biggest problem in 2021. Fast forward to today, and inventories are full and then some in certain sectors, while they remain quite lean in others. Below, we see the Inventory/Sales ratio has come off the bottom for the total system, and we expect the I/S ratio to continue to climb through the year with sales headwinds and some restocking still ongoing.

Inventories remain relatively low but on their way back to “normal”

A laggard on inventory correction is the automotive sector. The chart below shows still an all-time low I/S ratio, roughly 1/2 the typical cyclical trough level. I’d expect auto demand to be stronger for longer due to these significantly below-normal inventory levels. Plants should be running full schedules the remainder of 2022 at a minimum to see dealer inventories replenished closer to long-term average levels.

Bright spot: Auto demand will get push from inventory restock

And back to retail, the latest reading (chart below) of the Consumer Confidence Index, which we view more of a coincident than leading indicator is awful. And the index also fell a sharp 14% just from May to June, so it’s gotten worse in a hurry. This is why we have a slightly more negative view near-term on truckload and retail demand than some other modes, like LTL (less-than-truckload), which favor industrial shippers.

Consumer the most bearish we’ve seen in over 40 years

Source: University of Michigan

The consumer side of the economy has been hit first and hardest on a y/y comp basis, as that’s where most of the spending went last year with the stimulus checks. Target and other retailers have already made headlines for their growing inventory levels due to stalling/falling demand (and/or overordering). This will take time to unwind, and the likelihood of a longer lull in consumer spending is likely with rising interest rates, job cuts, rising rents, rising food prices, higher prices for most goods, and high energy prices.

Brief rate commentary - demand vs supply

We mentioned earlier that we believe “peak pain” is over for shippers, but it won’t mean (all) rates will plummet, or even go down in some modes (excluding fuel surcharges). Truckload is the most fragmented, so the transactional spot market will always see the biggest swings. Rates (ex-fsc) are >20% down from the beginning of the year in both dry van and reefer segments, while they remain near peak levels in flatbed due to seasonal support (more flatbed stuff is hauled in 2Q-3Q each year when the weather’s better). We’d expect flatbed rates to enjoy a similar decline come the fall, as the leaves turn and the Ravens look to get back to their winning ways. Unfortunately, the Orioles may very well be mathematically eliminated from playoff contention before flatbed rates dip.

Anyway, even with significant pullback in spot rates, TL contracts are still moving higher y/y today. Part of the reason is rising carrier costs, and another driver is the shift of freight from the spot market back into the contract market (i.e., some spot was necessitated by supply chain disruptions due to temporary demand changes and labor challenges), as shippers see more consistent freight flows. The spot market was also where the most capacity (small fleets) was added the last two years, so the additional capacity seeking what is now less available spot freight has led to a sizable drop in rates. Since supply moves more slowly than demand on the way up and on the way down, we expect spot rates to remain under pressure all year, until enough carriers are squeezed out to stabilize price levels.

Back to the carrier cost increases mentioned above. On the TL side, there’s been an increase in operating expenses due to higher driver wages and rising equipment costs (fuel is volatile and largely passed-through so not generally part of underlying rate discussions) that will help take TL contract rates higher through the next cycle. The excess supply will be reflected in spot market rates, so spot could fall again below contract for a period long enough to knock out weaker players. The higher carrier costs are also seen in other modes and have put a floor under LTL and parcel rates, as we expect 3%-4% rate hikes just to keep up with cost inflation.

LTL quickie

LTL is a much smaller market than TL, operates a hub-and-spoke model, and has a dear place in my heart. Much more to come on LTL down the line but wanted to throw a couple comments in here - couldn’t help it. This has been a great sector in recent years due to surging demand, better management pricing discipline, capacity constraints, and high barriers to entry. Given the heavier weight to industrial freight, you’ll likely hear better demand comments from LTL carrier this year (May tonnage still up y/y at ABF, Old Dominion, and Saia). And pricing will remain healthy, as fundamental capacity remains fairly constrained. That is slowly changing, though, for the first time in over a decade. LTL carriers are adding long-term capacity to their networks. In the chart below, we look at the terminal count data from public LTL carriers (who make up the majority of industry capacity). Yellow’s long-term decline (which actually continues with current double-digit y/y volume drops) drove this number lower from 2007-2014, and then after finding a bottom in 2020, real estate growth is back on the rise at public (and private) LTL carriers. Expect 2022 service center count to be up even more. Profits are at record levels, and capex is up big.

LTL terminal consolidation has reversed toward expansion

Source: Public carrier data

Industrial real estate has been hot, hot, hot. The most expensive markets where it’s hardest to find anything are SoCal, NJ, and Chicago. One carrier we spoke with has 40 real estate projects underway presently. Growth is causing most to trade up and vacate some existing space, and almost every carrier is building service centers, as there just are not enough available to buy.

That’s all for LTL today.

Next, the recession wrap-up.

Recession. It’s not a dirty word.

We’re likely already in a freight recession (not to be confused with an NBER-declared economic recession), if freight recession is defined as negative y/y growth in shipment volumes over several months, not necessarily for two straight quarters (although rail and parcel are already in recession under either definition). Last week, FedEx reported its F4Q22 results (March-May) and showed volume declines across all segments - Express, Ground, and Freight. Volumes are still healthy, just coming off last year’s highs.

The U.S. economy has not technically slipped into recession yet, but it will sooner rather than later. Lots of headlines these days with questions or declarations of a recession. Impending doom is often the implication. But it simply means there’s been an overheating of the system that needs to be corrected. Recession is the cool-down period before normal function resumes. It’s natural and should not be feared. Stress is not bad. It may be painful for the system temporarily, but it needs to move through it before growing to the next level.

Severe damage can be done, of course, by over-stressing the system to the point of collapse. But that’s hard to do. There are many signals before then that typically trigger a cool-down period, or recession, to allow for recovery.

Recessions are not all the same in depth or duration, but all are most problematic for those companies overstretched (too much leverage) and inflexible (high fixed costs), or just poorly run. Much of my writing will be about how to stay healthy as a company, so you can adapt easily to any kind of economic terrain and get stronger through the cycles.

“Prosperity is apt to prevent us from examining our conduct; but adversity leads us to think properly of our state, and so is beneficial to us.” - Bruce Lee

Funny how “the R Word” seemed like a bigger deal in my prior life as a sell-side analyst, where I watched the stock market moves every day. The media would have you believe it’s a bigger deal (fear—>clicks—>revenue), and Wall Street firms who want to encourage trading (fear—>trades—>revenue) are always looking for an excuse to scare people into buying or selling. Just like saying, “it’s getting dark,” or “it’s getting cold,” - “the economy is cooling” is just a heads-up on how to prepare for a temporary state that will naturally pass. At the companies I work with today, we are making sure we’re prepared to weather any storm and come out stronger, even growing through it if we can. Night is not bad, winter is not bad. Day follows night. Spring follows winter. Growth follows recession.

About the author: Dave Ross currently serves as Chief Strategy Officer at Ascent Global Logistics and EVP at Roadrunner. He is also a Director of Global Crossing Airlines. Prior to his current roles, he was Managing Director and Group Head of Stifel’s Transportation & Logistics Equity Research practice. Based in Miami, FL, he’s an artist, investor, advisor, proud dog dad, and serves on a few select non-profit boards.

** All opinions in this piece are solely those of the author and not intended to represent those of Ascent Global Logistics or Roadrunner or other affiliated entities.

Excellent article. Great insight. Todd Koffman, West Brow Capital.